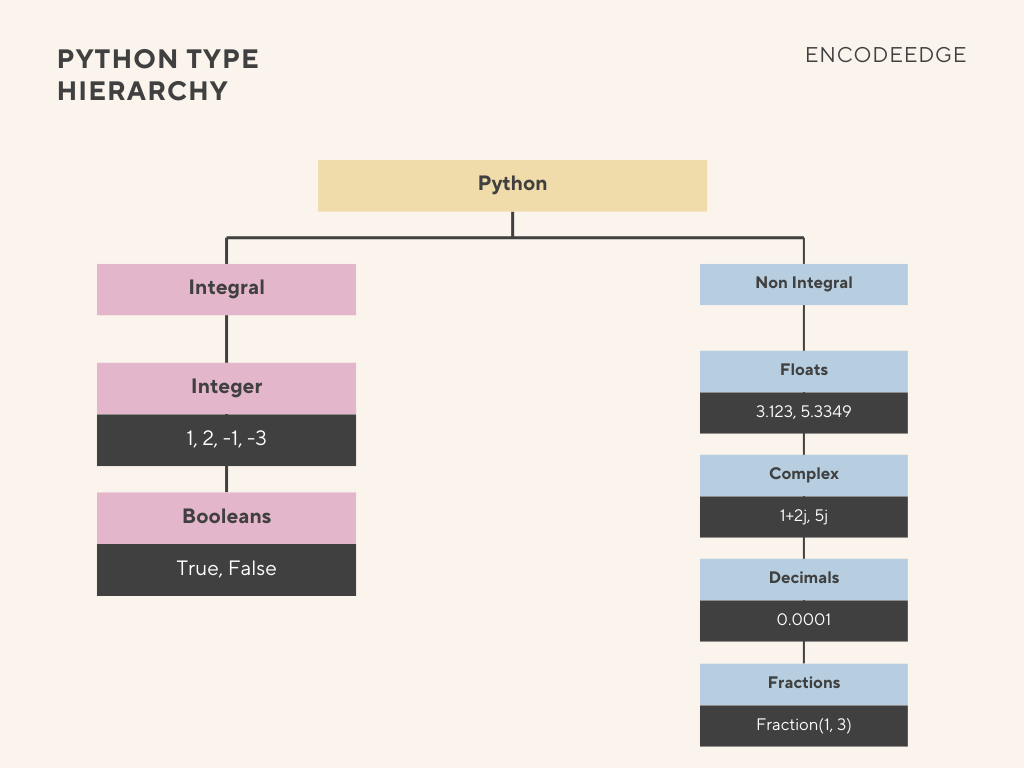

Type Hierarchy

Type hierarchy defines what data types are supported by Python, i.e different type of data that can be created and stored in Python.

Before that lets have a look at one of the most important concept of objects in python. In this course we will see many data types, operators like int, float, dictionary, None, (’+’, ’*’), functions, Classes etc. But one thing is common, i.e they are all objects (instance of classes) in python. That means they all have a memory address.

def fun(a):

return a*2

class b :

abc = "xyz"

print("Type of function fun is : {0} and it's address is {1}".format(type(fun), id(fun)))

print("Type of class b is : {0} and it's address is {1}".format(type(b), id(b)))

print("Type of function fun is : {0} and it's address is {1}".format(type(type), id(type)))Type of function fun is : <class 'function'> and it's address is 4357881712

Type of class b is : <class 'type'> and it's address is 5471267584

Type of function fun is : <class 'type'> and it's address is 4320241760As we can see above each of the function or class created is an object of a certain class. In Python 3, every class implicitly inherits from object. Whether it is a built-in type like int or str, or a custom class we define ourself, if we trace the inheritance tree all the way to the root, we will find object. The method __mro__ (method resolution order) can be used to trace the order.

print("The full type lineage of int is ", int.__bases__)

print("The full type lineage of int is ", bool.__bases__)

# Let's define a CustomType:

class MyCustomType:

pass

print(MyCustomType.__mro__)

x = 10

s = "Hello"

def my_func(): pass

print("{0} is an instance of {1} and it's full lineage is {2}".format(x, isinstance(x, object), type(x).__mro__))

print("{0} is an instance of {1} and it's full lineage is {2}".format(x, isinstance(s, object), type(s).__mro__))

print("{0} is an instance of {1} and it's full lineage is {2}".format(x, isinstance(my_func, object), type(my_func).__mro__))

The full type lineage of int is (<class 'object'>,)

The full type lineage of int is (<class 'int'>,)

(<class '__main__.MyCustomType'>, <class 'object'>)

10 is an instance of True and it's full lineage is (<class 'int'>, <class 'object'>)

10 is an instance of True and it's full lineage is (<class 'str'>, <class 'object'>)

10 is an instance of True and it's full lineage is (<class 'function'>, <class 'object'>)Let’s have a look at a subset of data type which are most commonly used.

Numbers

Numeric types are broadly divided into two main categories: Integral and Non-Integral.

Integral Numbers

These represent integers, bool etc.

Integers (int):

Integers are positive and negative numbers, like -3, -1, 1, 2, 3.

Integers are objects of int class. These are of variable length and take variable size of memory based on the size of the integer.

If we look at the variable int_1 which references value 0. we can see it requires an overhead of 24 bytes.

import sys

print("Size of int 0 : ", sys.getsizeof(0))Size of int 0 : 24Similarly if we look at value of flag and flag_false which is of bool type. The objects is an instance of int type and consume memory that of integer 0 and 1.

flag = True

flag_false = False

print("flag is of type : ",type(flag))

print("flag is an instance of : ",isinstance(flag, int))

print("Size of bool True : ", sys.getsizeof(flag))

print("Size of bool True : ", sys.getsizeof(flag_false))

flag is of type : <class 'bool'>

flag is an instance of : True

Size of bool True : 28

Size of bool True : 24Operations on Integer

We can perform various mathematical operations on int variable. Some of these like, Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication, exponentiation (positive exp.) results in int values. whereas division result in a float.

print("Addition : ",type(12 + 7), "\nSubtraction : ", type(1 - 9), "\nMultiplication : ", type(7 * 4), "\nDivision : ", type(9 / 3))Addition : <class 'int'>

Subtraction : <class 'int'>

Multiplication : <class 'int'>

Division : <class 'float'>int class has 2 constructor, which are described below :

help(int)Help on class int in module builtins:

class int(object)

| int([x]) -> integer

| int(x, base=10) -> integer

|

| Convert a number or string to an integer, or return 0 if no arguments

| are given. If x is a number, return x.__int__(). For floating point

| numbers, this truncates towards zero.

|

| If x is not a number or if base is given, then x must be a string,

| bytes, or bytearray instance representing an integer literal in the

| given base. The literal can be preceded by '+' or '-' and be surrounded

| by whitespace. The base defaults to 10. Valid bases are 0 and 2-36.

| Base 0 means to interpret the base from the string as an integer literal.

| >>> int('0b100', base=0)print(int(11.5))

print(int("1001"))11

1001The second constructor can be used to convert string based on a given base by default it is base 10.

int("1010", base=2)10There are some built in methods that can be used to convert these from one to the other e.g. bin, oct and hex

print("Convert to Binary : ",bin(10), "\nConvert to Octal : ", oct(10), "\nConvert to Hexadecimal : ", hex(10))Convert to Binary : 0b1010

Convert to Octal : 0o12

Convert to Hexadecimal : 0xaBooleans (bool):

Stores truthy and falsy value (True or False). Interestingly, in Python, booleans are actually a subclass of integers.

print("type of bool value True is : ",type(True), "it's id is ",id(True), " and it's int equivalent is :",int(True))type of bool value True is : <class 'bool'> it's id is 4347331776 and it's int equivalent is : 1

Internally the truthiness of an object is determined as per how it implements the __bool__() method.

help(bool)Help on class bool in module builtins:

class bool(int)

| bool(x) -> bool

|

| Returns True when the argument x is true, False otherwise.

| The builtins True and False are the only two instances of the class bool.

| The class bool is a subclass of the class int, and cannot be subclassed.

|

| Method resolution order:

| bool

| int

| objectSo, as per the resolution order, truthy nature will be determined based on __bool__() or __len__() implementation in the class or parent one.

# Any non-zero numeric value is truthy.

from fractions import Fraction

from decimal import Decimal

print("-----Any Non-zero numeric value is truthy:----")

print("boolean of 120 :",bool(120), "\nboolean of 21.6 : ", bool(21.6), "\nboolean of Fraction(7, 8) : ", bool(Fraction(7, 8)), "\nboolean of Decimal('0.9') : ", bool(Decimal('0.9')))

#Any zero numeric value is falsy:

print("-----Any Zero numeric value is falsy:----")

print("Boolean of 0 is :",bool(0), "\nBoolean of 0.0 is :",bool(0.0), "\nBoolean of Fraction(0,1) is :",bool(Fraction(0,1)), "\nBoolean of Decimal('0') is :",bool(Decimal('0')), "\nBoolean of 0j is :",bool(0j))

# For Sequence and Collection types, empty containers are falsy, non-empty containers are truthy.

print("-----Empty containers are falsy----")

print("Boolean of '' ",bool(''), "\nBoolean of ()",bool(()), "\nBoolean of []", bool([]), "\nBoolean of {}", bool({}), "\nBoolean of set()", bool(set()), "\nBoolean of frozenset()", bool(frozenset()))

print("-----Non-empty containers are truthy----")

print("Boolean of 'Hello'", bool('Hello'),"\nBoolean of (1,2)", bool((1,2)),"\nBoolean of [3,4]", bool([3,4]),"\nBoolean of {'a':1}", bool({'a':1}), "\nBoolean of {1,2}",bool({1,2}), "\nBoolean of frozenset([3,4])",bool(frozenset([3,4])))-----Any Non-zero numeric value is truthy:----

boolean of 120 : True

boolean of 21.6 : True

boolean of Fraction(7, 8) : True

boolean of Decimal('0.9') : True

-----Any Zero numeric value is falsy:----

Boolean of 0 is : False

Boolean of 0.0 is : False

Boolean of Fraction(0,1) is : False

Boolean of Decimal('0') is : False

Boolean of 0j is : False

-----Empty containers are falsy----

Boolean of '' False

Boolean of () False

Boolean of [] False

Boolean of {} False

Boolean of set() False

Boolean of frozenset() False

-----Non-empty containers are truthy----

Boolean of 'Hello' True

Boolean of (1,2) True

Boolean of [3,4] True

Boolean of {'a':1} True

Boolean of {1,2} True

Boolean of frozenset([3,4]) TrueNon-Integral Numbers

Numbers which are not integer i.e have fraction component or like complex numbers.

Floats (float):

The most common non-integral type, used for real numbers like 3.14. They are usually implemented as C doubles in the underlying C language.

To represent real number, we can use float class in python. Let’s have a look at the help method to see how to define float values

help(float)Help on class float in module builtins:

class float(object)

| float(x) -> floating point number

|

| Convert a string or number to a floating point number, if possible.

|

...

the float class uses one constructor that takes a number or string and then tries to convert it to a floating point number.\

print("float(10) = ", float(10), "\nfloat('10') = ", float("10"), "\nfloat('10.5') = ", float("10.5"))

print("0.3 = ", 0.3)

print("0.3 upto 25 decimal point ",format(0.3, '.25f'))float(10) = 10.0

float('10') = 10.0

float('10.5') = 10.5

0.3 = 0.3

0.3 upto 25 decimal point 0.2999999999999999888977698Although some fractions are not stored exactly when using floats and for those cases we can either using Fraction or Decimal to store these.

This can cause equality issues since not all real numbers have an exact float representation, as described below\

var_1 = 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1

var_2 = 0.3

print("Is var_1 == var_2 : ", var_1 == var_2)

print('0.1 --> {0:.25f}'.format(0.1))

print('var_1 --> {0:.25f}'.format(var_1))

print('var_2 --> {0:.25f}'.format(var_2))Is var_1 == var_2 : False

0.1 --> 0.1000000000000000055511151

var_1 --> 0.3000000000000000444089210

var_2 --> 0.2999999999999999888977698In cases when the numbers have an exact float representation, this works fine.

var_1 = 0.125 + 0.125 + 0.125

var_2 = 0.375

print("Is var_1 == var_2\n", var_1 == var_2)

print('0.125 --> {0:.25f}'.format(0.125))

print('var_1 --> {0:.25f}'.format(var_1))

print('var_2 --> {0:.25f}'.format(var_2))Is var_1 == var_2

True

0.125 --> 0.1250000000000000000000000

var_1 --> 0.3750000000000000000000000

var_2 --> 0.3750000000000000000000000Thus we have to be careful when doing, arithmetic operations on decimal numbers.

To compare equality when using floats, we can make use of isclose() method from math library.

from math import isclose

help(isclose)Help on built-in function isclose in module math:

isclose(a, b, *, rel_tol=1e-09, abs_tol=0.0)

Determine whether two floating point numbers are close in value.

rel_tol

maximum difference for being considered "close", relative to the

magnitude of the input values

abs_tol

maximum difference for being considered "close", regardless of the

magnitude of the input values

Return True if a is close in value to b, and False otherwise.

For the values to be considered close, the difference between them

must be smaller than at least one of the tolerances.

-inf, inf and NaN behave similarly to the IEEE 754 Standard. That

is, NaN is not close to anything, even itself. inf and -inf are

only close to themselves.

The isclose method accepts two optional parameters to fine-tune your comparison: rel_tol and abs_tol.

- rel_tol (Relative Tolerance): This scales based on the magnitude of the input values. It is best used when you want to check if two numbers are close within a certain percentage (e.g., “within 5% of each other”).

- abs_tol (Absolute Tolerance): This is a fixed threshold independent of the input size. It is essential when comparing numbers very close to zero, where relative comparison can fail.

In general, we can use isclose() method as defined below :

var_1 = 0.0000001

var_2 = 0.0000002

var_3 = 263547364.01

var_4 = 263547364.02

print('var_1 = var_2:', isclose(var_1, var_2, abs_tol=0.0001, rel_tol=0.01))

print('var_3 = var_4:', isclose(var_3, var_4, abs_tol=0.0001, rel_tol=0.01))var_1 = var_2: True

var_3 = var_4: TrueComplex (complex):

Numbers that have both a real and an imaginary part, such as .

Python’s built in class provides support for complex numbers. We can create a variable of complex type, either by defining the real and imaginary part of the number or by providing the imaginary number itself.

comx_1 = complex(1, 2)

comx_2 = 1 + 2j

print("real part of complex number : ",comx_1.real, "is of type ",type(comx_1.real))

print("imaginary part of complex number : ",comx_2.imag, "is of type ",type(comx_2.imag))real part of complex number : 1.0 is of type <class 'float'>

imaginary part of complex number : 2.0 is of type <class 'float'>Since the numbers of a complex type is stored as float, do remember the caveat of the same as discussed in this article under floats and decimal section.

Decimals (Decimal):

Provide greater precision and control over floating-point arithmetic compared to standard floats. Decimals are useful in situations where we need precision and exact representation of decimal values.

While working with the Decimal module in python, it provides a context that is used to adjust how we work with the module. majorly, we can set the precision, rounding algorithm while working with arithmetic operations. Context can be local or global.

Let’s look at how to work with the decimal module in python

# import the decimal module and check the default global context

import decimal

global_ctx = decimal.getcontext()

print("precision by default for the global context is : ",global_ctx.prec)

print("rounding by default for the global context is : ",global_ctx.rounding)

# We set these values as per our requirement

global_ctx.prec = 6

global_ctx.rounding = decimal.ROUND_CEILING

print("Updated precision for the global context is : ",global_ctx.prec)

print("Updated rounding for the global context is : ",global_ctx.rounding)

precision by default for the global context is : 28

rounding by default for the global context is : ROUND_HALF_EVEN

Updated precision for the global context is : 6

Updated rounding for the global context is : ROUND_CEILINGwhen using the local context we can make use of the with command.

with decimal.localcontext() as context:

context.prec = 10

print('local prec = {0}, global prec = {1}'.format(context.prec, global_ctx.prec))local prec = 10, global prec = 6Let’s look at how to use Decimal module in practice. We have set the precision at 2. Now when we create two new variable of Decimal type, the values are stored as is with the exact precision. Only when we perform any arithmetic operation, the precision kicks in and the result will be in the desired precision value.

decimal.getcontext().prec = 2

var_1 = Decimal('0.23489')

var_2 = Decimal('0.71287')

print("var_1 : ", var_1)

print("var_2 : ", var_2)

print("var_1 + var_2 = ", var_1 + var_2)var_1 : 0.23489

var_2 : 0.71287

var_1 + var_2 = 0.95The Decimal constructor can convert a variety of values. When converting values it’s better to avoid using floats and use string instead as for values for which we don’t have exact representation in base 2, will be captured as is by decimal. look at the below example of ‘0.3’.\

import decimal

from decimal import Decimal

print("Decimal constructor with integer value : ",Decimal(15))

print("Decimal constructor with string value : ",Decimal('15.67'))

# Don't use float value to construct Decimal, as it may lead to precision issues. Best way is to use string value.

print("Decimal constructor with float value : ",Decimal(0.3))

print("Decimal constructor with string value : ",Decimal('0.3'))

Decimal constructor with integer value : 15

Decimal constructor with string value : 15.67

Decimal constructor with float value : 0.299999999999999988897769753748434595763683319091796875

Decimal constructor with string value : 0.3The Decimal class implement variety of mathematical function and we should use that when performing any mathematical functions. We could use the one’s from math library also, but it will convert the decimal type to float and will perform the operation, which will be contrary to why we are suing the Decimal class. So best to avoid it and use the ones defined with the Decimal class.

var_1 = Decimal('4.2')

print("var_1.log10() : ", var_1.log10()) # base 10 logarithm

print("var_1.ln() : ", var_1.ln()) # natural logarithm (base e)

print("var_1.exp() : ", var_1.exp()) # e**a

print("var_1.sqrt() : ", var_1.sqrt()) # square rootvar_1.log10() : 0.6232492903979004632209830566

var_1.ln() : 1.435084525289322621899838647

var_1.exp() : 66.68633104092514164502173465

var_1.sqrt() : 2.049390153191919676644207736Drawbacks :

Apart from the ones already covered, using Decimal class takes up more memory than floats and also is slower than floats operations and is noticeable when performing large operations.

import sys

from decimal import Decimal

var_1 = 0.3

var_2 = Decimal('0.3')

print("var_1 size stored as float :",sys.getsizeof(var_1))

print("var_2 size stored as Decimal :",sys.getsizeof(var_2))var_1 size stored as float : 24

var_2 size stored as Decimal : 104Fractions (Fraction):

Represent rational numbers as a fraction (numerator and denominator). These are used when we need exact arithmetic, for instance, ensuring is precisely equal to 1, which standard floats cannot guarantee due to their finite precision.

We can use Fraction class from module fraction to implement rational numbers. Using the help method on the Fraction class we can have a peek on how to use it.

help(Fraction)Help on class Fraction in module fractions:

class Fraction(numbers.Rational)

| This class implements rational numbers.

|

| In the two-argument form of the constructor, Fraction(8, 6) will

| produce a rational number equivalent to 4/3. Both arguments must

| be Rational. The numerator defaults to 0 and the denominator

| defaults to 1 so that Fraction(3) == 3 and Fraction() == 0.

|

| Fractions can also be constructed from:

|

| - numeric strings similar to those accepted by the

| float constructor (for example, '-2.3' or '1e10')

|

| - strings of the form '123/456'

|

| - float and Decimal instances

|

| - other Rational instances (including integers)

|

| Method resolution order:

| Fraction

| numbers.Rational

| numbers.RealAs we can see we can pass the input in variety of ways to get a Fraction object.

from fractions import Fraction

# Using integers

print("fraction of int 1 : ", Fraction(1))

print("fraction of int 1/3 : ", Fraction(1, 3))

# Using rational numbers (i.e numerator/denominator)

x = Fraction(6, 5)

y = Fraction(3, 2)

# 6/5 / 3/2 --> 6/5 * 2/3 --> 4/5

print("fraction of 6/5 / 3/2 : ", Fraction(x, y))

# Using floats

print("fraction of float 0.125 : ", Fraction(0.125))fraction of int 1 : 1

fraction of int 1/3 : 1/3

fraction of 6/5 / 3/2 : 4/5

fraction of float 0.0.125 : 1/8The numerator and denominator can be looked at by using below.

x = Fraction(22, 7)

print("Numerator of x is : ", x.numerator)

print("Denominator of x is : ", x.denominator)Numerator of x is : 22

Denominator of x is : 7In case when the value passed in not a finite value, then the Fraction class will approximate the values, we have another method i.e limit_denominator, that can be used to limit the denominator to a desired value.

For example. for value of pi , if we don’t restrict the denominator the value returned will try to be exactly equal to the decimal value. But we can restrict the denominator to be below 7 and that will return us

import math

frac_1 = Fraction(math.pi)

print("Value of pi, without limiting the denominator", frac_1)

print(format(float(frac_1), '.25f'))

frac_2 = Fraction(math.pi).limit_denominator(10)

print("Value of pi, limiting the denominator to 10 :", frac_2)

print(format(float(frac_2), '.25f'))Value of pi, without limiting the denominator 884279719003555/281474976710656

3.1415926535897931159979635

Value of pi, limiting the denominator to 10 : 22/7

3.1428571428571427937015414

Fig. 1 : Python Type Hierarchy for Integrals

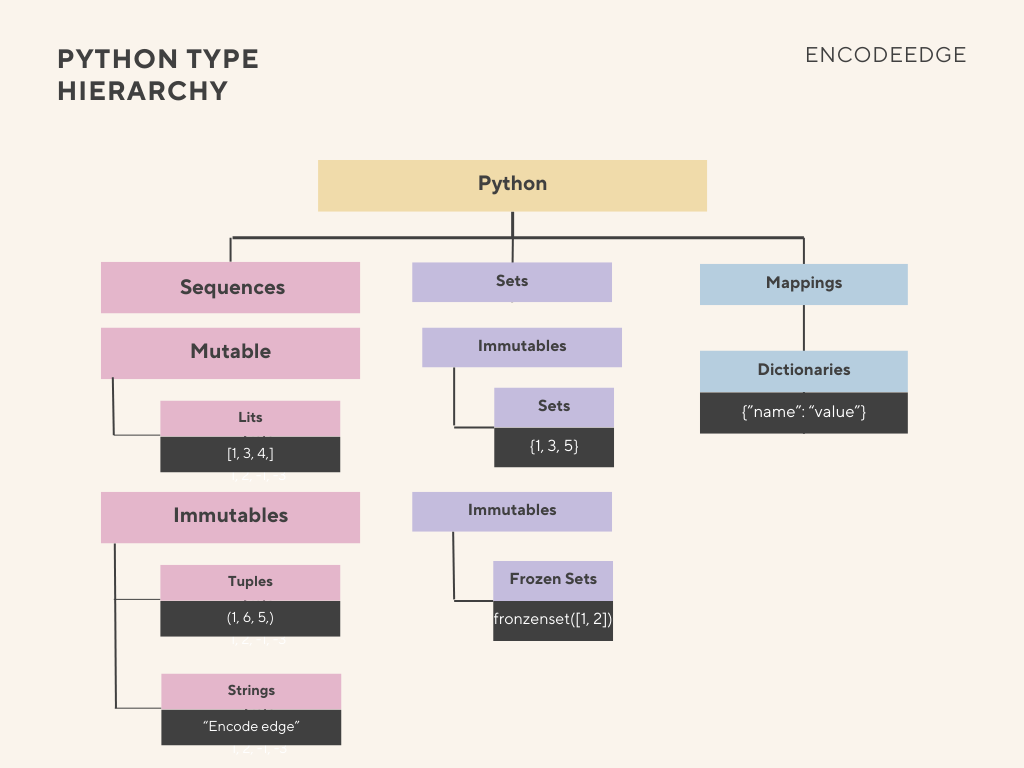

Collections

Collections are data structures that group multiple items together. They are broadly categorized into Sequences, Sets, and Mappings.

Sequences (Ordered)

Sequences store elements in a specific order, and they can be further divided into mutable and immutable types.

- Mutable Sequences:

- Lists (list): The most flexible and common sequence type; they can be changed after creation.

- Immutable Sequences:

- Tuples (tuple): The immutable variant of lists.

- Strings (str): Also a sequence type, where each element is a character, and they are immutable.

Sets (Unique and Unordered)

Sets store unique elements and are primarily implemented as hash maps.

- Mutable Sets (set): Standard sets that allow elements to be added or removed.

- Immutable Sets (frozenset): The immutable equivalent of sets. Because they are immutable, they can be used as elements in other sets or as dictionary keys.

Mappings (Key-Value)

- Dictionaries (dict): These are also implemented similarly to sets—as hash maps—but they store data as key-value pairs instead of just keys.

Fig. 2 : Python Type Hierarchy for Collections

Callable

A callable is anything that can be invoked or called using the parentheses ().

- Functions:

- User-Defined Functions.

- Built-in Functions: Such as len() or open().

- Instance Methods: Functions defined inside a class that are called on an instance of that class (e.g., list.append()).

- Classes: The classes themselves are callable, as calling them instantiates an object.

- Class Instances: An object created from a class can be made callable by defining the special __call__ method.

- Generators: Used for iteration, yielding values one at a time.

Singletons

These are unique objects that exist independently or serve special purposes:

- None : A singleton object representing the absence of a value. Any variable set to None always points back to the same memory address for the None object.

- NotImplemented : A special value used, for example, when defining comparison methods (__lt__, __gt__) in classes to indicate that a comparison between two different types is not supported.

- Ellipsis Operator (…) : An operator (represented as Ellipsis() in memory) that can be used for things like slicing, especially in advanced sequence types or libraries like NumPy.

NoneType

It is a built-in variable of type “NoneType” and is a reference to an object instance of NoneType. Python’s memory manager will use shared reference as NoneType objects are immutable.

While None is used to represent an “empty” value or missing data (similar to a null pointer), it remains a real object within Python’s memory. Consequently, the memory manager handles every assignment to None by using a shared reference to the same object instance.

print(None, "is of Type {0}, It's Hex is is : {1}".format(type(None), hex(id(None))))

var_1 = None

print("var_1 is of Type {0}, It's Hex is is : {1}".format(type(var_1), hex(id(var_1))))

var_2 = None

print("var_2 is of Type {0}, It's Hex is is : {1}".format(type(var_2), hex(id(var_2))))

print("var_1 == var_2 : ", var_1 == var_2)

print("var_1 is var_2 : ", var_1 is var_2)None is of Type <class 'NoneType'>, It's Hex is is : 0x100f53a50

var_1 is of Type <class 'NoneType'>, It's Hex is is : 0x100f53a50

var_2 is of Type <class 'NoneType'>, It's Hex is is : 0x100f53a50

var_1 == var_2 : True

var_1 is var_2 : TrueFor collections, an empty one does have the same collection type, instead of None Type.

str_1 = ""

list_1 = []

tup_1 = ()

print("str_1 is of Type {0}".format(type(str_1)))

print("list_1 is of Type {0}".format(type(list_1)))

print("tup_1 is of Type {0}".format(type(tup_1)))

str_1 is of Type <class 'str'>

list_1 is of Type <class 'list'>

tup_1 is of Type <class 'tuple'>Statically typed and Dynamically typed

Statically typed languages, such as Java, C++, and Swift, require a variable’s data type to be explicitly declared at the time of creation, and this type cannot be changed later. For example, in a statically typed language, if a variable named myVar is declared as a String (e.g., String myVar = “hello”;), it can only hold string values. Attempting to assign an integer value, like myVar = 10, would result in a type error because the variable has been declared as a String and is incompatible with the integer type. However, assigning another string value, like myVar = “abc”, is acceptable.

In contrast, Python is a dynamically typed language. In Python, variables are simply references or pointers to objects in memory, and the variables themselves do not have a fixed, inherent type. For instance, when you write my_var = ‘hello’, the variable my_var is just referencing a string object with the value ‘hello’. This flexibility allows the same variable to later reference an object of a completely different type without causing an error. For example, executing my_var = 10 is perfectly valid; the variable my_var simply stops pointing to the string object and starts pointing to an integer object with the value 10. To determine the type of the object a variable is currently referencing, Python provides the built-in type() function, which looks up the object at the memory location the variable is pointing to and returns that object’s type.

# Lets assign string to variable a and check its type

a = "hello"

print("Type of a is : ", type(a))

# Lets reassign variable a to a number and check its type

a = 10

print("Type of a is : ",type(a))

# Now lets assign a lambda function to variable a and check its type

a = lambda x: x**2

a(2)

print("Type of a is : ",type(a))Type of a is : <class 'str'>

Type of a is : <class 'int'>

Type of a is : <class 'function'>